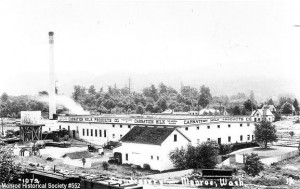

The Condensery Smokestack

The tall concrete smokestack, which stands at the east side of Monroe near the intersection of Main Street and State Rte 2 across from Tavelers Park, is all that remains of a large condensery that once stood on the site of the Monroe Shopping Center.

In 1908, [the Monroe Commercial Club] saw their chance to attract a milk condensing plant of the Pacific Coast Condensed Milk Company (also known as Carnation). The membership was determined that the importance of securing this industry cannot be overestimated and the chances are good. It now remains to go after it hard. Within a few months the club contacted local farmers and conducted a “cow canvas” and raised a cash fund of $6000 to purchase a factory site which was then donated to the company. The condensery was built in 1908 out of locally milled lumber. Farmers brought in better cattle to improve their herds, and within a month of completion of the factory over $140,000 worth of farming acreage had been sold. Soon the factory was handling the milk of over 5000 cows and shipping 26 carloads of product monthly.*

The main building was 110 feet wide and 220 feet long with a stockroom half that size (110-feet square) on the second floor. The brick powerhouse was 42 feet wide and 100 feet long with room for six boilers although only two were initially installed. A 50,000 gallon wooden tank stored water piped in from the Skykomish River. At first, the plant had a single metal smokestack 60 feet high, but in an expansion the following year, a second, matching smokestack was added.

It was not until about 1919 that the concrete smokestack that still stands was built to replace the two metal stacks. It is 150 feet tall and almost eleven feet in diameter at the base. There were eleven milk pickup routes in the area, and the stables for the horses and wagons were on the northeast corner of the property. In addition, the steamboat Carnation No. 1 went as far as south as Tolt (present-day Carnation) on the Snoqualmie River to pick up milk. The steamboat was 55 feet long with an 11-foot beam and a draft of only 18 inches.

The incoming milk was held in 2,000 gallon tanks and then drawn off into glass-lined kettles and steamed. From there it was drawn into vacuum pans (or condensers). The condensed milk was cooled in the refrigeration room, then canned and sealed. After sealing, the cans went to a retort and were heated to sterilizing temperatures before being labelled and boxed.

Increased competition in the 1920s forced consolidation of operations to Mount Vernon and the Monroe plant turned more to the production of casein , a hard plastic-like substance manufactured from milk. The factory was finally closed in late 1929 and it remained idle throughout the Depression. When the United States entered World War II, flax was declared a strategic material. In early 1942, the Pacific Fiber Flax Association bought the plant in early early 1942 and began to remodel it into a flax processing plant at a cost of $65,000. Local farmers were persuaded to grow flax and by the end of 1943, the plant employed 40 workers turning the flax into linen.

The plant had only been in operation three weeks when 600 tons of flax stored in the building ignited by spontaneous combustion at 1 a.m., March 23, 1944. The Monroe Fire Department worked hard to keep the fire from spreading beyond the plant, but by dawn all that remained of the plant was the concrete smokestack. The plant was only partially insured and was never rebuilt.

It was decided it would be too difficult and dangerous to remove the smokestack, which remains today as a Monroe landmark. The chimney cleanout at the base on the south side has been closed up as well as the rectangular flue opening on the west side. On the east side, about halfway up, is the remains of an old ENCO sign for the service station that was once located at its base.

–from information compiled by Bill Wojciechowski

*from the 13th annual Getting Acquainted With Our Valleys supplement, Historical Edition, to the Monroe Monitor and Sultan Valley News, June 2, 1982, pages 20-21, by Nancy Moore Rockafellar.